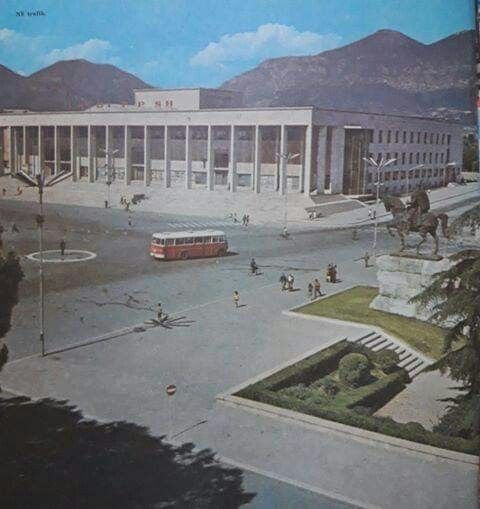

Skenderbeg Square is the heart of Tirana, Albania

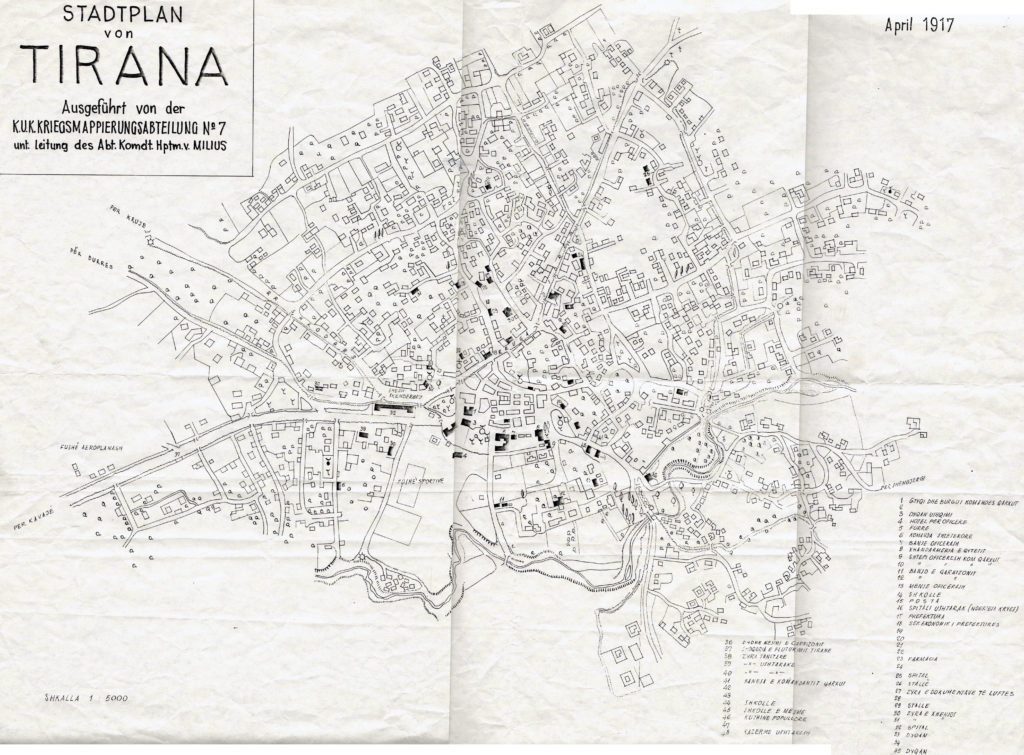

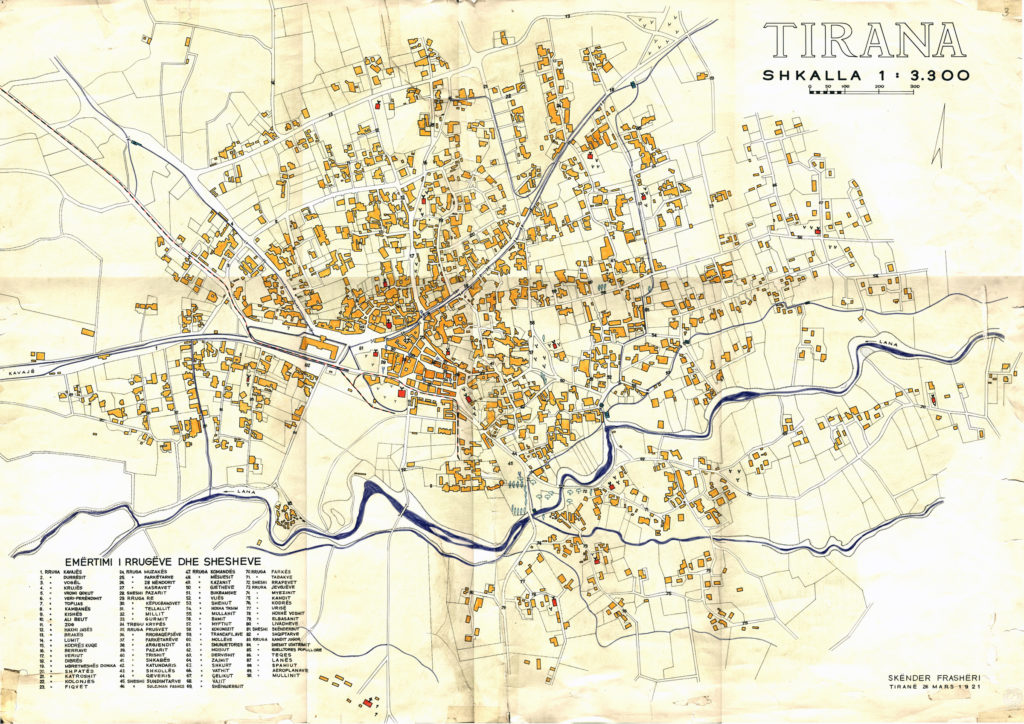

Skenderbeg Square is the heart of Tirana. It appears on the first known map of Tirana as Sheshi Skenderbej. The name Skenderbeg has been spelled in several different ways over the years. However, Skenderbeg Square probably had little importance as a focal point of the city until well into the 20th century. Perhaps, it had some importance as the confluence of the main roads from Durrës and Kavajë. But, as noted in the 2010 Doctoral Thesis INFLUENCES OF POLITICAL REGIME SHIFTS ON THE URBAN SCENE OF A CAPITAL CITY, CASE STUDY: TIRANA by Indrit Bleta:

“Regarding the social and economic structure of the city, the inhabitants lived,

worked and carried on almost all their daily life within the same urban quarter. These

compact quarters were basically created upon ethnic and religious affiliation, and were

almost self-sufficient communities with which the individual identified, thus physical

and social space, were almost identical. These neighbourhoods had the exact

convenient human scale and types of social networks in which the inhabitant could

find a uniquely individual space.”

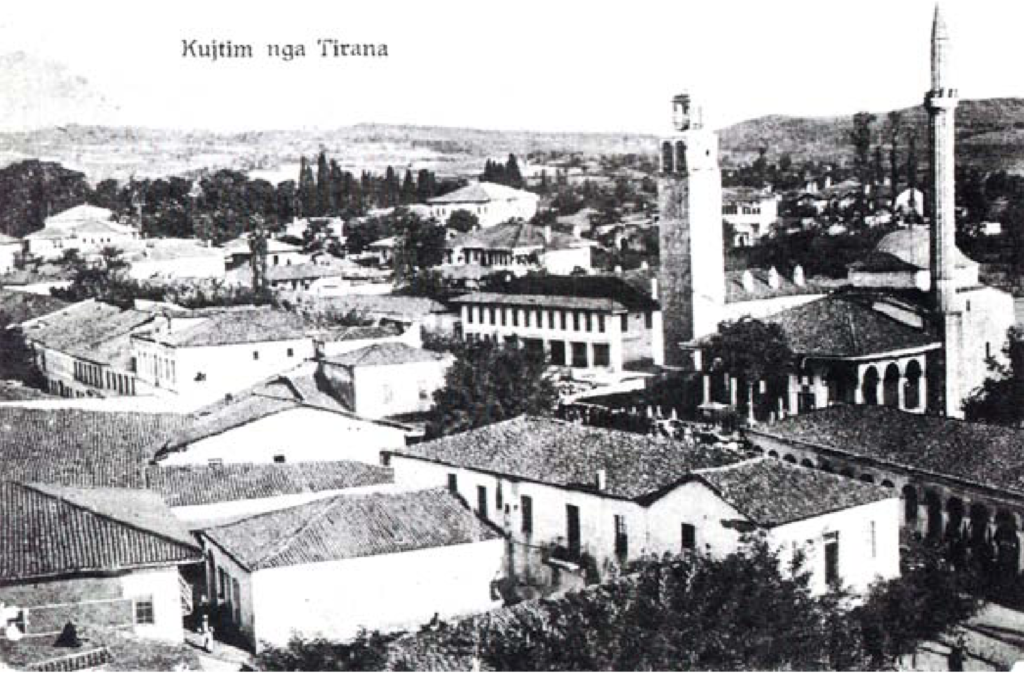

The Old Bazaar was the heart of Tirana, Albania

As noted by Bruno Castiglioni in “Tirana – Appunti sulla capitale dell’Albania all’alba del nuovo regime,” Bollettino

della Reale Società Geografica Italiana VI, no. 1 (January 1941):19,”

“The heart of the city is, as we saw, the Bazaar, that is a quarter sui generis,

distinct from all others, little changed today compared to the descriptions we

receive from the days of turkish Tirana. It is a maze of streets and alleys, lined

with small huts at the slightest expression, mostly with only ground floor, with

the shop opening on the road with and the back room, when necessary used

for storage or workshop.“

Another description of Tirana by Bernd Jurgen Fischer in his book King Zog and the struggle for stability in Albania, East European Monographs 159 (New York: Boulder, 1984), 19. follows:

“The new capital was actually little more than an enlarged Moslem

village… …and consisted primarily of a bazaar used for hanging offenders of

the peace, four mosques, several barracks and a number of legations. Tirana

gave the appearance of a gold rush town in the late 19th century American

West, with its saloons, gambling casinos and ever present guns and gunbelts.

A rickity Ford progressing slowly along the muddly unpaved unlite streets was

the only sign of the twentieth century.“

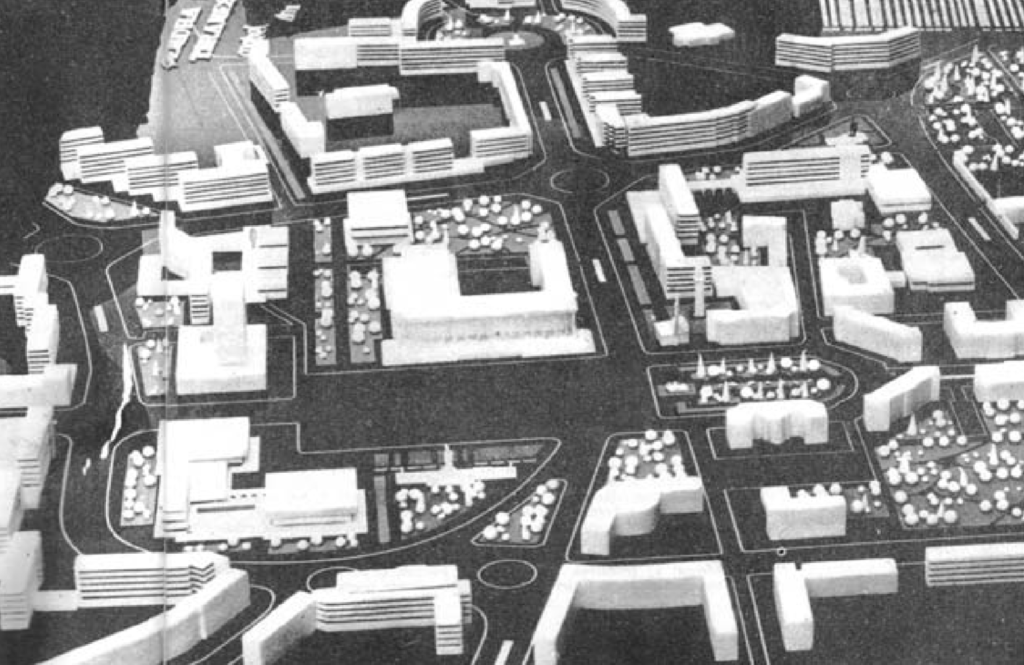

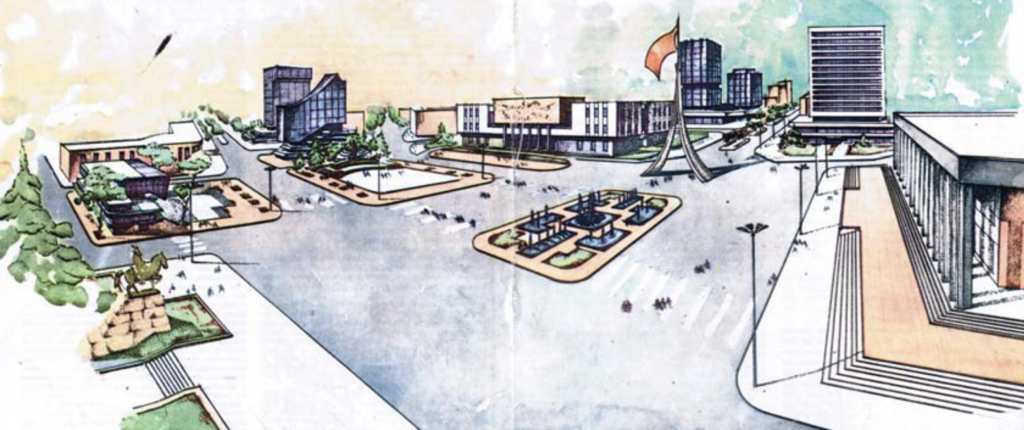

Differing perspectives on the urban future of Tirana

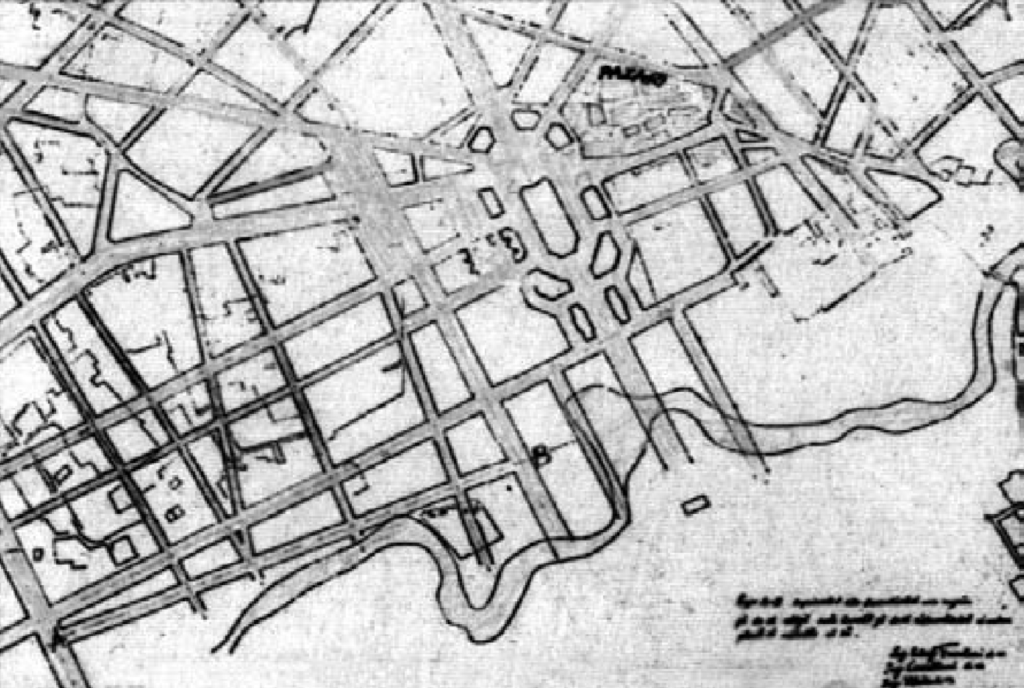

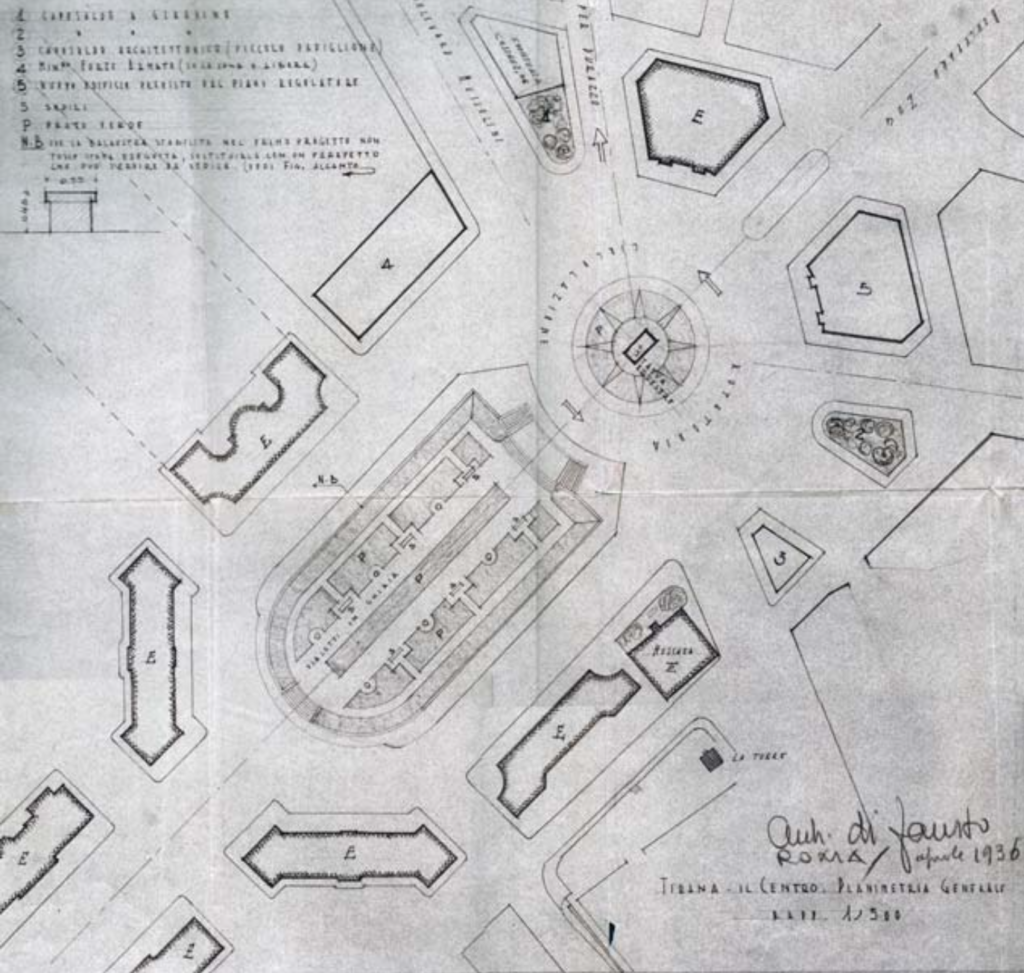

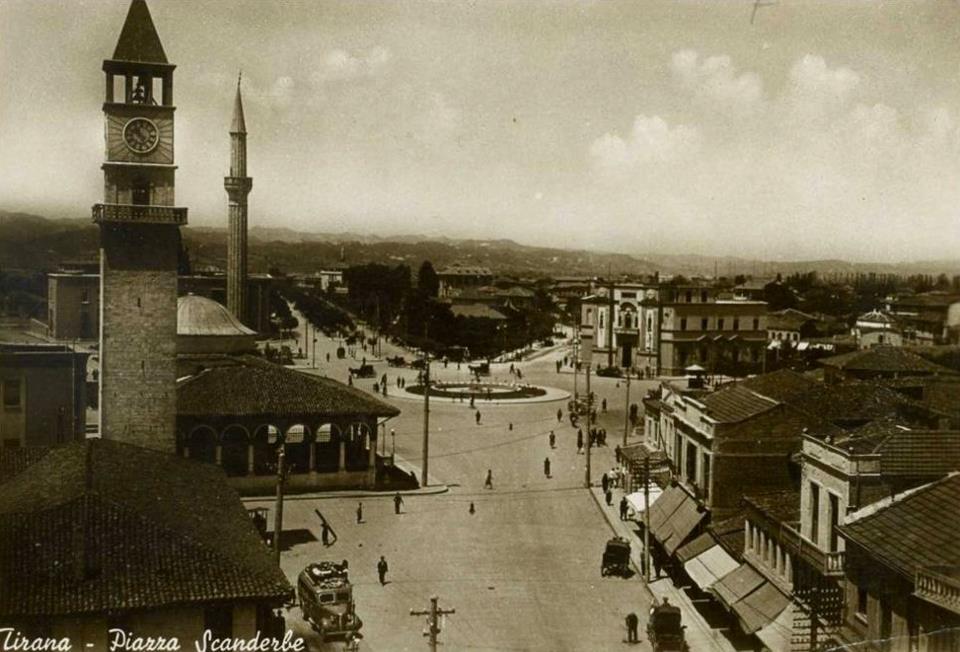

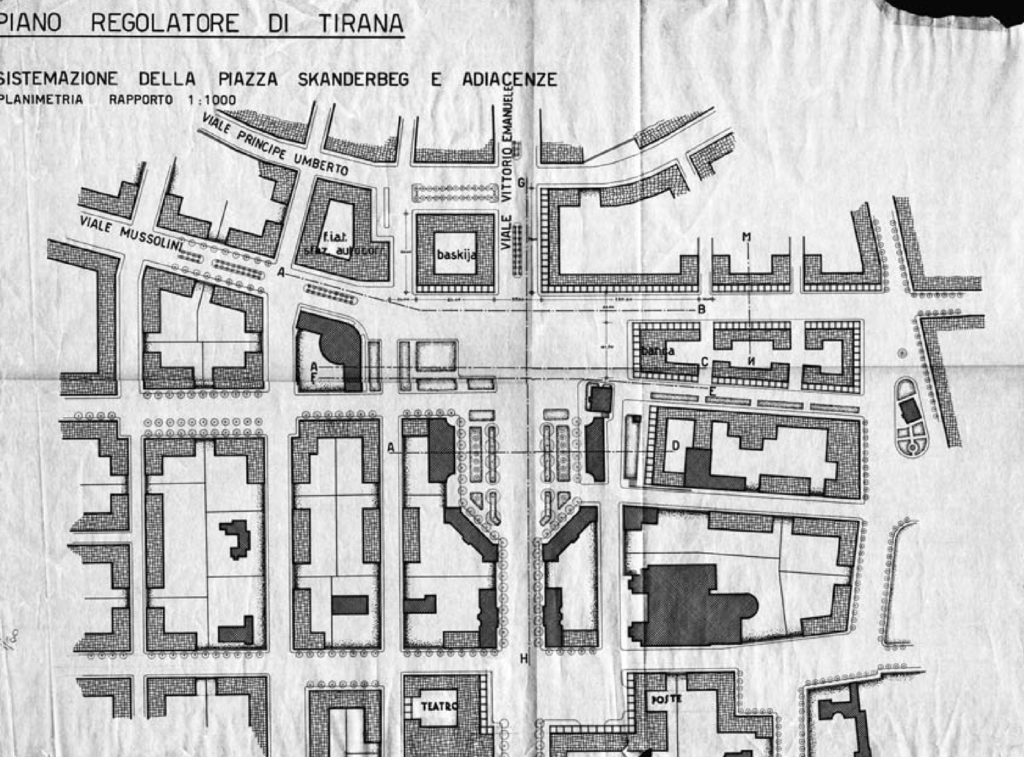

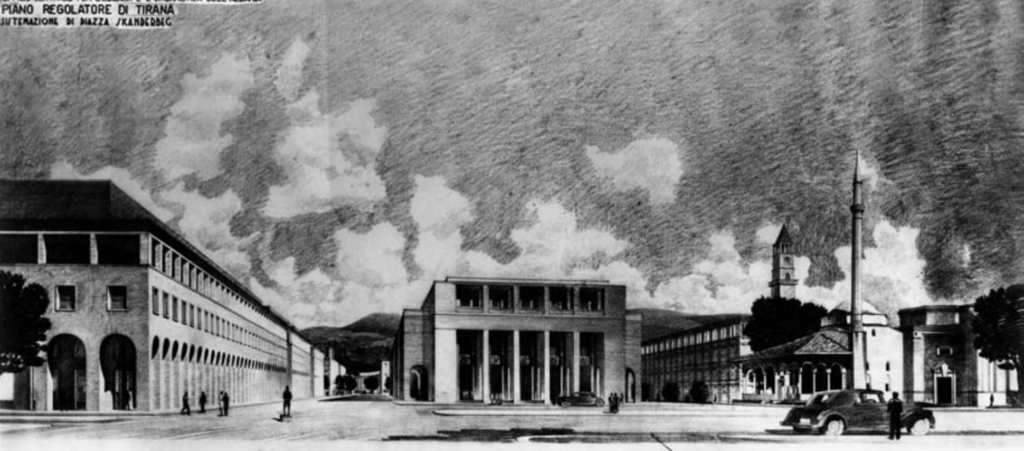

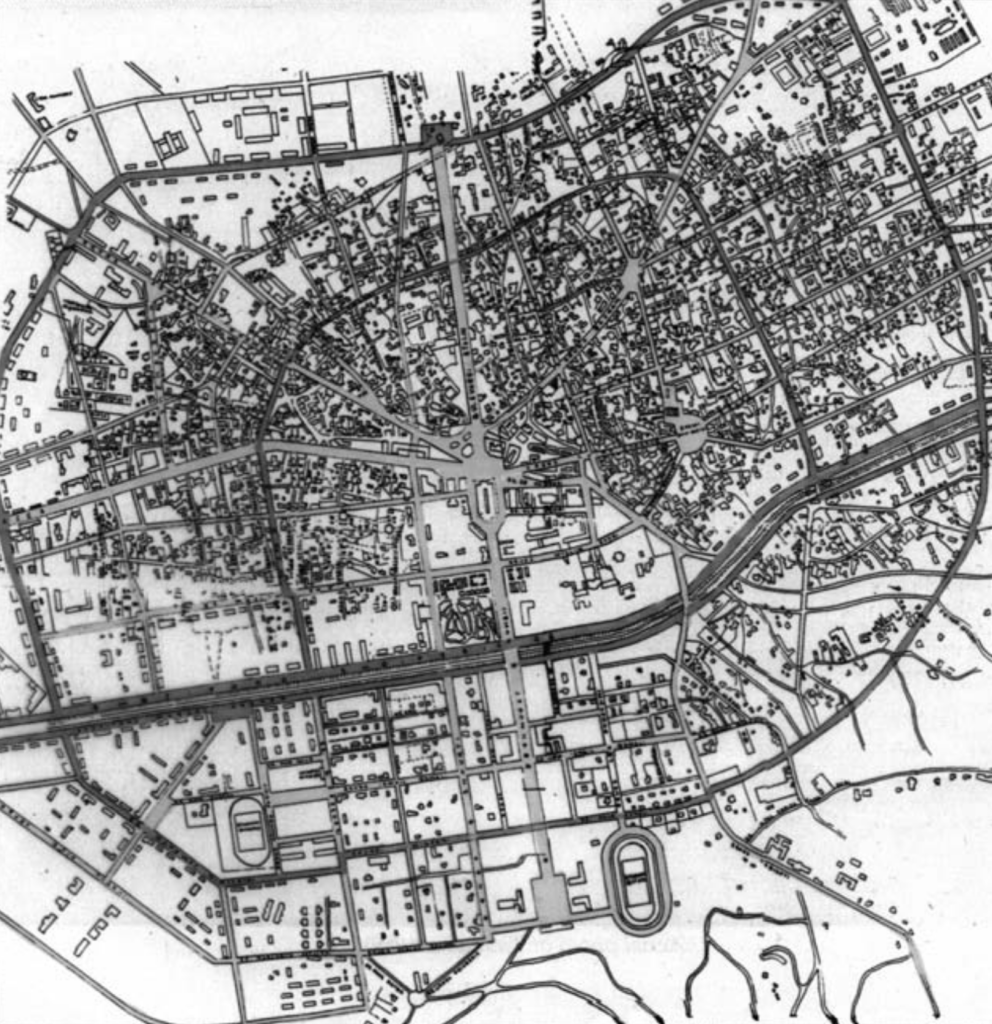

There were differing perspectives in the mid 1920’s on how to develop the urban center of Tirana. One idea was to leave the historical core intact and one was to rebuild the town’s core as well as develop the open areas to the south. In the end, the ideas by Italian architect Armando Brasini won out. His idea was to build a grand avenue on a north-south axis through the heart of the city and place government and civil buildings along it. In the end, his ideas were too vast and costly to carry out. But his idea of expressing the greatness of the new Roman Empire under the Fascists through architecture and urban design did prevail.

A unifying urban plan for Tirana

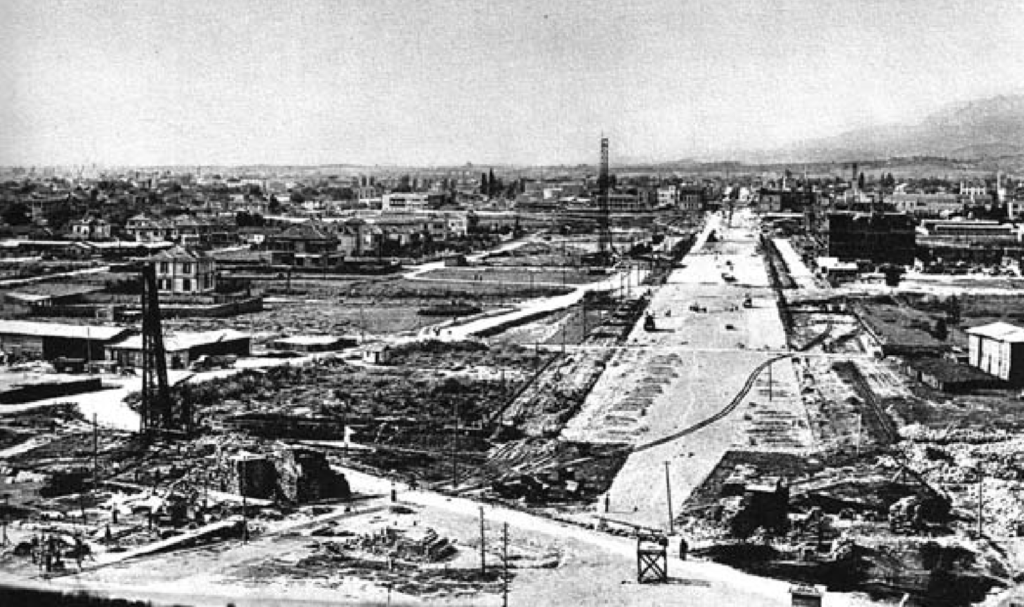

“This plan brought together the axis ideated by Brasini and later elaborated by di Fausto and Köhler, the plans for the Square of the Ministries of di Fausto, the Hippodamic layout of the Tirana e Re district of Köhler, and a new feature: the extension of the boulevard northward finalizing it with a huge stadium project. Although Giusti attributes this project to Köhler, it doesn’t appear on the procured materials. By this addition, the boulevard had a central point – the Square of the Ministries – and two ends, the political one: King’s palace, and the sportive one: the national Stadium. Ironically, the northern part of the boulevard was the first to be realised, although projected nearly six years later than the southern one. The decree 2241 of September 9, 1929 marks the beginning of the works for this part of the boulevard (Fig. 3.2.2) which was named ‘Zog I'” – Indra Bleta, referencing Aliaj, Besnik, Keida Lulo, and Genc Myftiu, eds. Tirana, the challenge of urban

development. 31

King Zog builds his boulevard first!

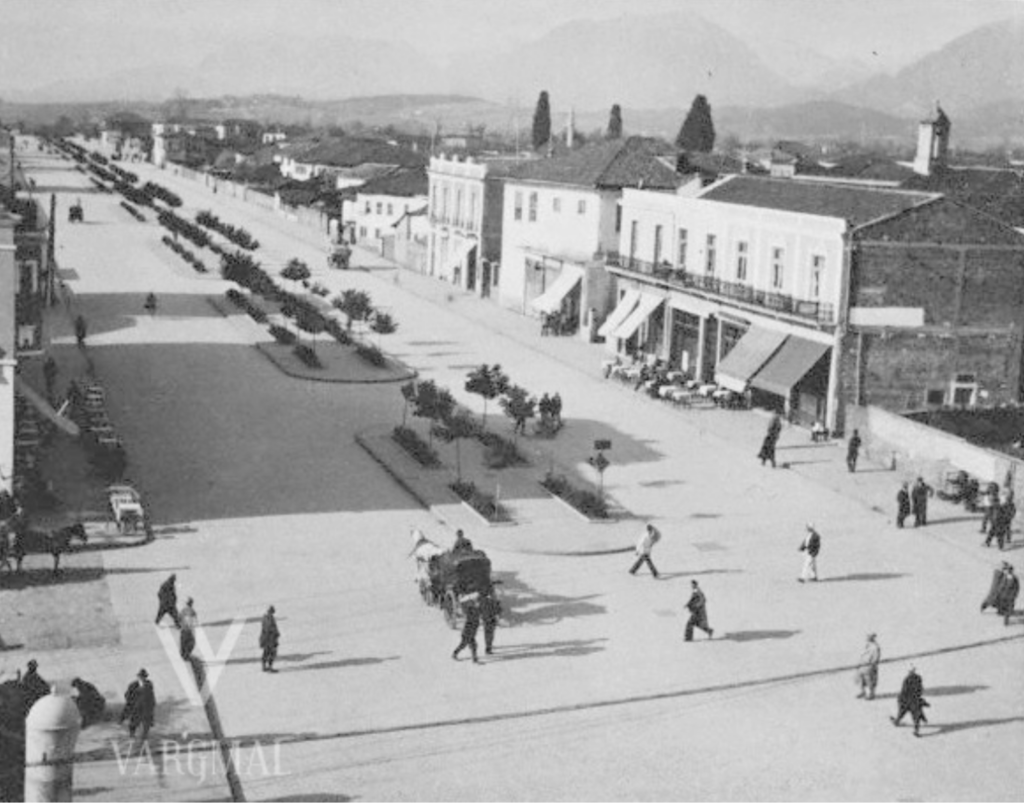

Even though the planning and design of Skenderbeg Square, the heart of Tirana, and the boulevard to the south preceeded King Zog’s planning and implementation of his boulevard by several years, his priority was to construct Bulevardi Zogu I first. Having consolidated enough power feel confident in moving forward, his plan envisioned a long, broad boulevard going north from Skenderbeg Square and ending at his palace.

The rest of the grand plan is implemented later.

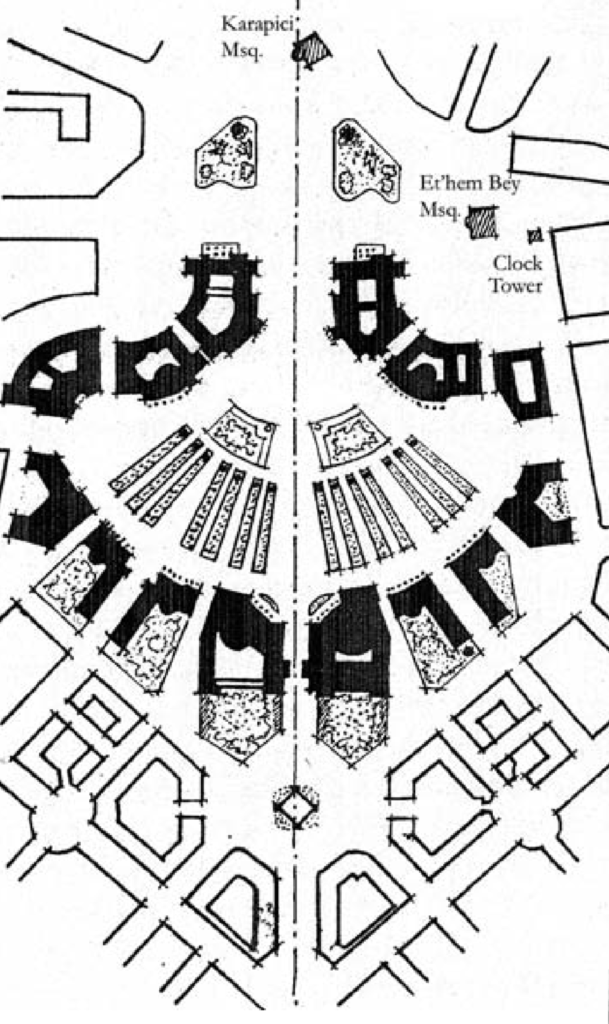

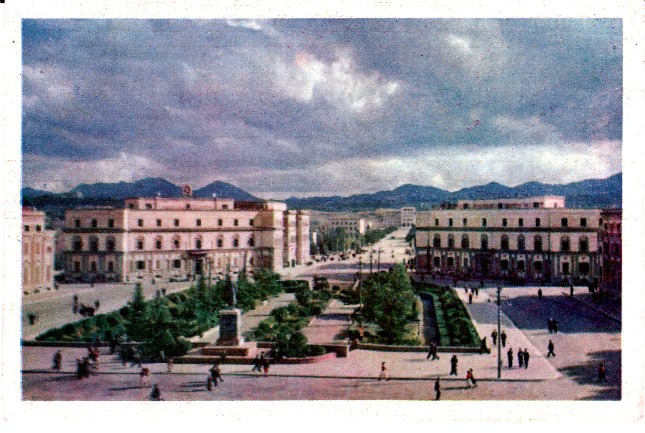

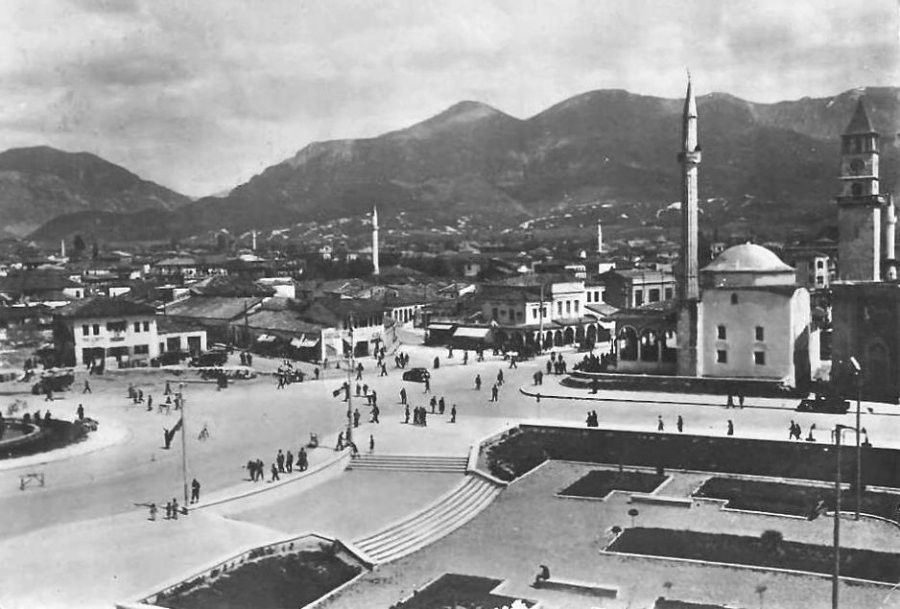

“The main boulevard entered the square from the empty areas south of it, split in two branches around a sunken garden which join each other again to exit the square as the northern part. The garden was sunk so that the buildings around it could be perceived higher than they were, and on design notes the architect prescribed planting wide-crown trees to achieve the maximum shadow possible without harming the effect over the buildings. To build the northern part of the square and part of the boulevard it took the demolition of the Karapici Mosque (previously an important part of Brasini’s plan, laying upon the central axis) and some 19th century hans and shops of the old Bazaar.” -Indrit Bleta referencing Koço Miho, Trajta të profilit urbanistik të qytetit të Tiranës (Tiranë: 8 Nëntori, 1987), 118.

National Bank

“During the kingdom years, other several buildings of high quality have been built by Italian architects and contractors. Two of these are of exceptional value: the National Bank Headquarters’ building for being almost a turn point from the neoclassical design to more simplified modern lines and the Circolo Italo – Albanese Scanderbeg, for being the first building where prefabricated construction techniques were applied resulting in a rationalist design. Inaugurated in 1938, the National Bank building, designed by Vittorio Ballio Morpurgo, is located at the western part of Skënderbej Square.” – Indrit Bleta

Tirana during the Italian occupation from 1939-1943

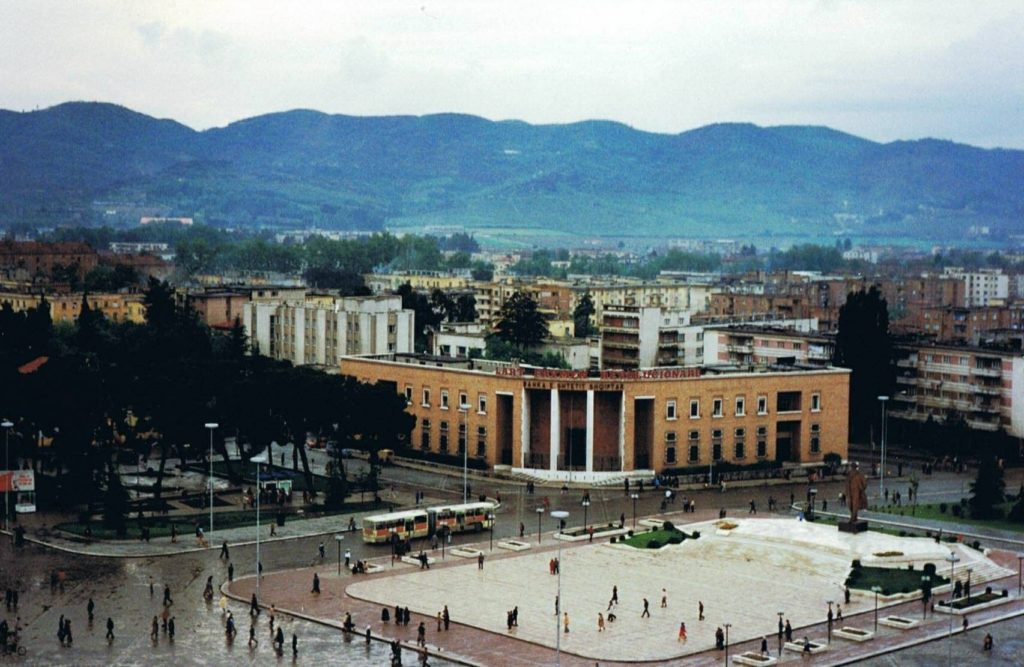

The break with Fascist architecture and planning after WW2.

“The reversal of power and ideology which took place in Albania was a drastic transition process from fascist (or its vassal system) to socialist authority. Nonetheless, in spatial terms this transition meant the inevitable presence of earlier eras’ material traces. The existing buildings were the only possible administrative infrastructure and it would have been unwise not to use them, so they had to change their connotations. The past was present more than anywhere else in the city on the main boulevard, and people could use old meanings and memories that did not fit with the new regime’s scheme. Nevertheless, the remains of the previous politico-urban regime were more

easy to be absorbed and even forgotten mainly for two reasons. First, it was present for only a short time, so the image created was easy to be changed, and also because the amount of people who lived with that image was a minority of what would be the demographics of the socialist capital. Second, most of the image created by the

previous regime, which was mainly state buildings and public works, served easily as a base for the future planning, both being dictatorial systems.

The main directives given by the state were that the cities were to be designed “… avoiding any influence from the revisionist and bourgeois ideology, aiming the concentration and gathering of the buildings, thus saving the arable land used for agrarian purposes, especially the grain fields…”. Enver Hoxha, “From the speech given in the commission set up for the issue of urbanism of the city of Tirana and other cities of the country – 19.02.1948, ”458. “… to create the conditions for a better life for the people, who look at the new living conditions, to watch the changes coming from the aid of popular power, watch how the state strives for it and gives results. ” – Indrit Bleta

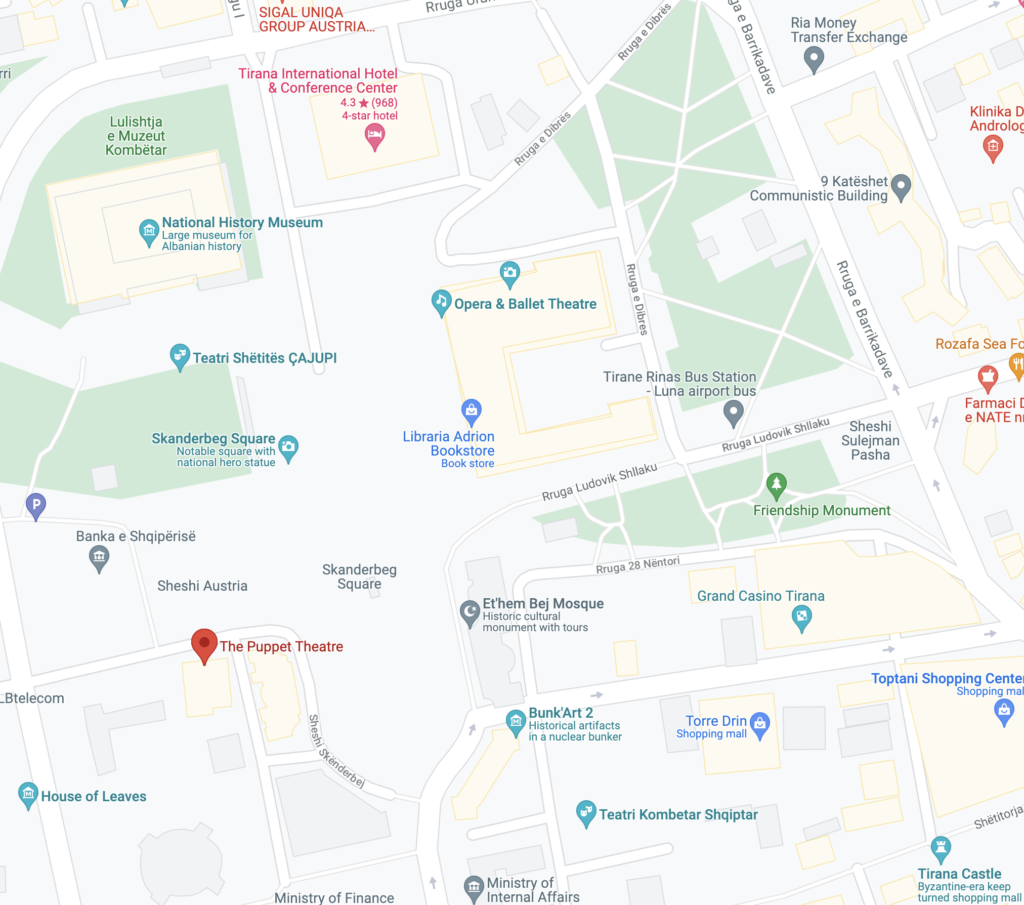

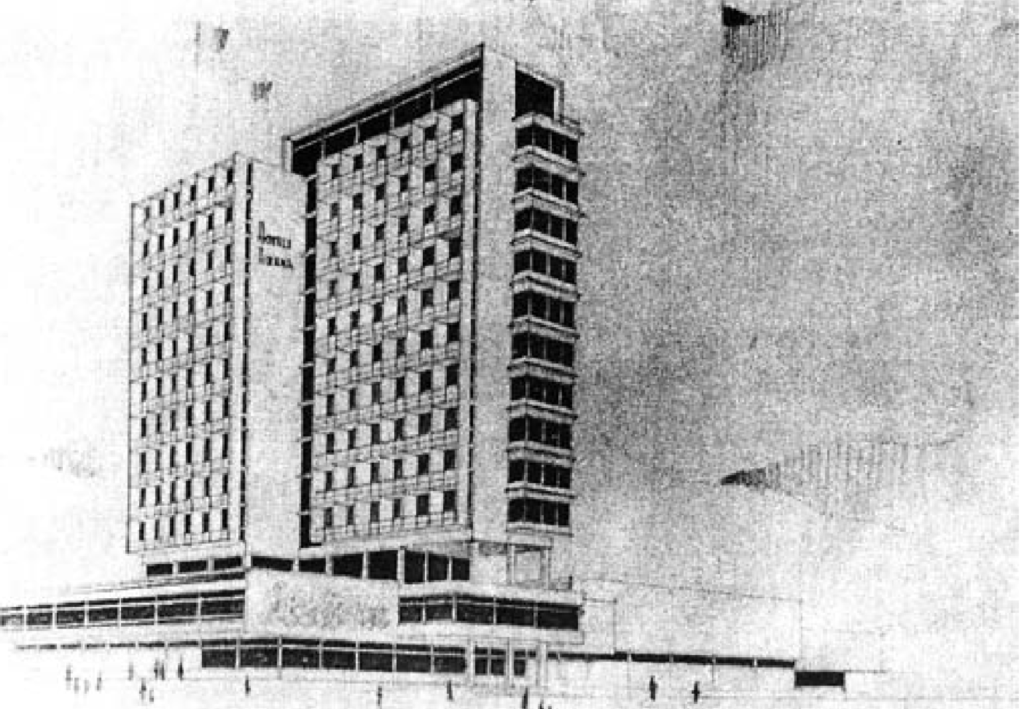

The old bazaar, which had been in the same location for centuries, was demolished and replaced by the Palace of Culture, a gift from the Soviet Union. Then, Enver Hoxha broke ties with the Soviets and all Soviet engineers and architects left Albania in 1961. It was a great burden to take on the cost of the project so it was a relief when the Chinese stepped in at this time. The destruction of the old bazaar next to Skenderbeg Square, the heart of Tirana, signaled that the communist regime had disassociated itself from the city’s past.

The design process for the National History Museum began in 1976. In front of the museum, was to be placed a statue of Enver Hoxha on a pedestal, which would be visible in the center of Durrës Street as one approached Skenderbeg Square. In 1979, the old municipal building was blown up to make way for construction. The new museum was inaugurated on November 8, 1981.

The need to take the city from dictators and return it to the people

Throughout the 20th century, various powers worked to make the heart of Tirana in their own image. First, there were Italian architects invited by the nascent Albanian government, Then came the dictator/monarch King Zog, who wished to cement his grandeur. Again, the Italians came and designed the city with their greatness in mind, not the with the comfort of the people who lived there. Afterwards, came the socialist dictatorship that first assumed the styles of the Soviet Union. Then when they burned that bridge, they attempted to cultivate a class of native architects, only to persecute them, put them on trial and jail or deport them. What materialized was a vast public space, subservient to the regime, but disjointed and serving no unified purpose.

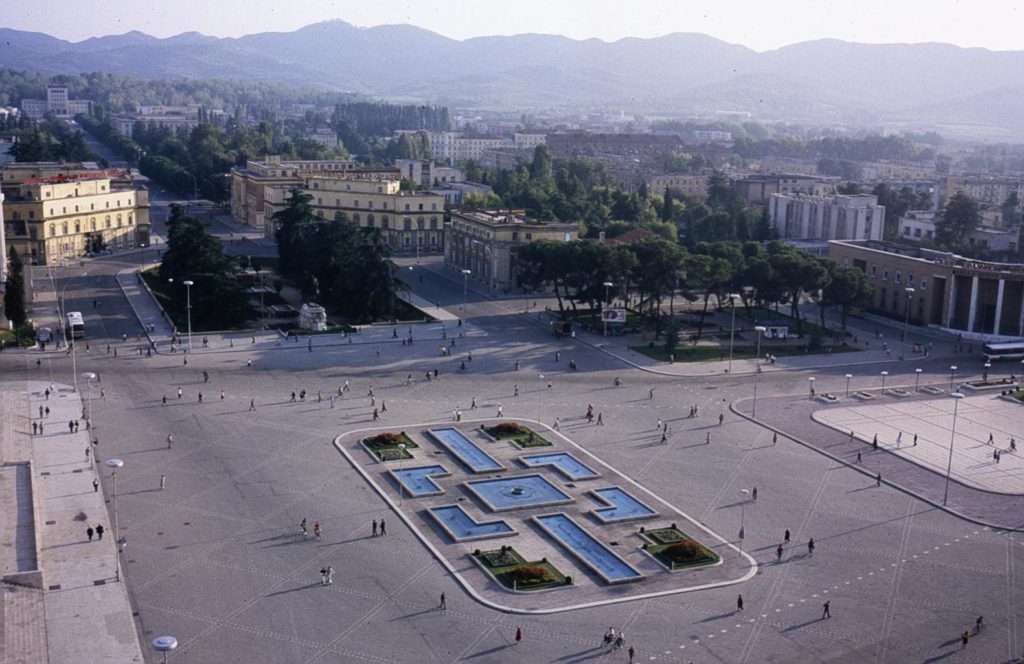

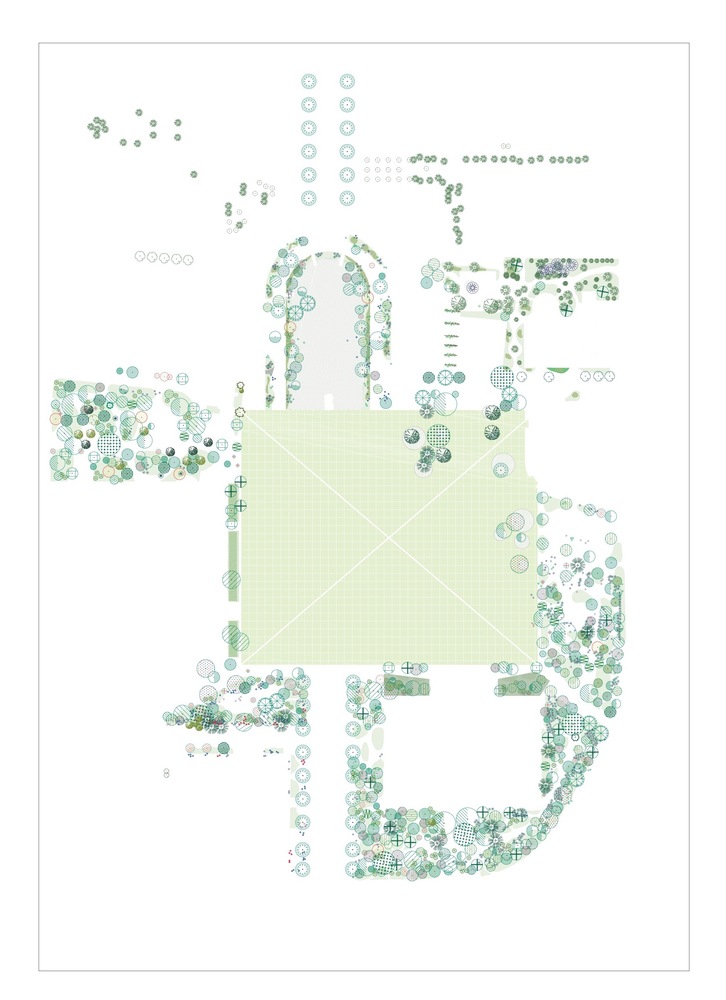

In 2008, the Belgian Design firm 51N4E won the competition to redesign Skenderbeg Square. It is amazing to realize that 25% of Albania’s population lives within 2.5 km of Skenderbeg Square, according to Topos Magazine, in a thoughtful article entitled Framework for Participation. In a sense, the new design recaptured Skenderbeg Square as the heart of Tirana.

The new design of Skenderbeg Square returns the heart of Tirana to the people

[…] the book is a collaboration between IABR, the Belgian urban design office 51N4E that designed Skenderbeg Square in Tirana, Dutch design firm FABRIC, the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, the TU […]